In early February 2022, a LinkedIn post by Nicolas Pirsoul caught my eye because it proposed an innovative solution for representing the significant number of people who don’t vote in elections for parliament. The crux of his proposal was:

Given that, in an electoral democracy, non-voters are not represented (to my knowledge, no parliaments have “empty seats” representing people abstaining), why not represent people abstaining from voting with randomly selected citizens?

Despite New Zealand being ranked one of the strongest democracies in the world, declining voter turnout is a long-run trend. If it can’t be turned around by changing to a proportional voting system or by ongoing efforts to make enrolling and voting easier and more convenient, surely it’s time to consider other approaches.

And while Nicolas may be the first person to suggest that non-voters be represented in parliaments by randomly selected citizens, the idea fits with what has been dubbed the ‘deliberative wave’. Since the 1980s, authorities around the world have been using random selection to select people to be democratic representatives in citizens’ juries and assemblies charged with finding solutions to public problems. The evidence is that these randomly selected groups are very good at learning about issues, weighing up the pros and cons of different approaches and coming up with collective recommendations about what should be done.

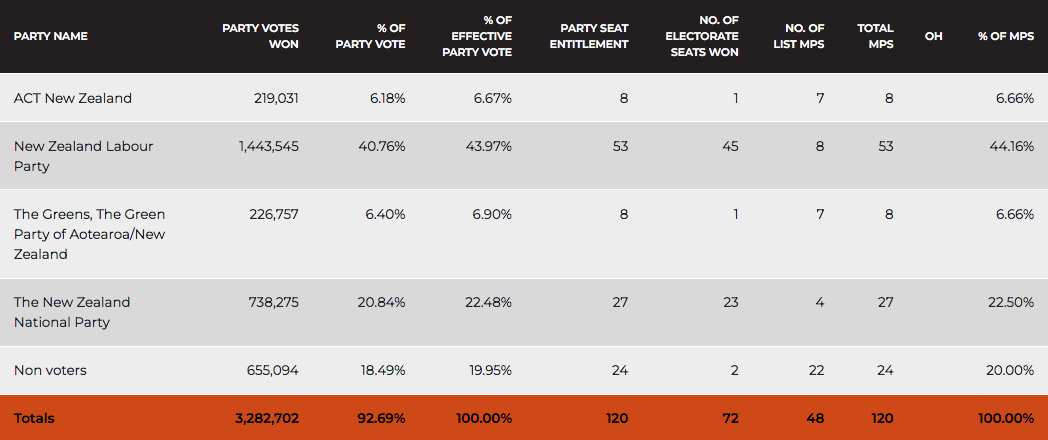

Application to the 2020 general election

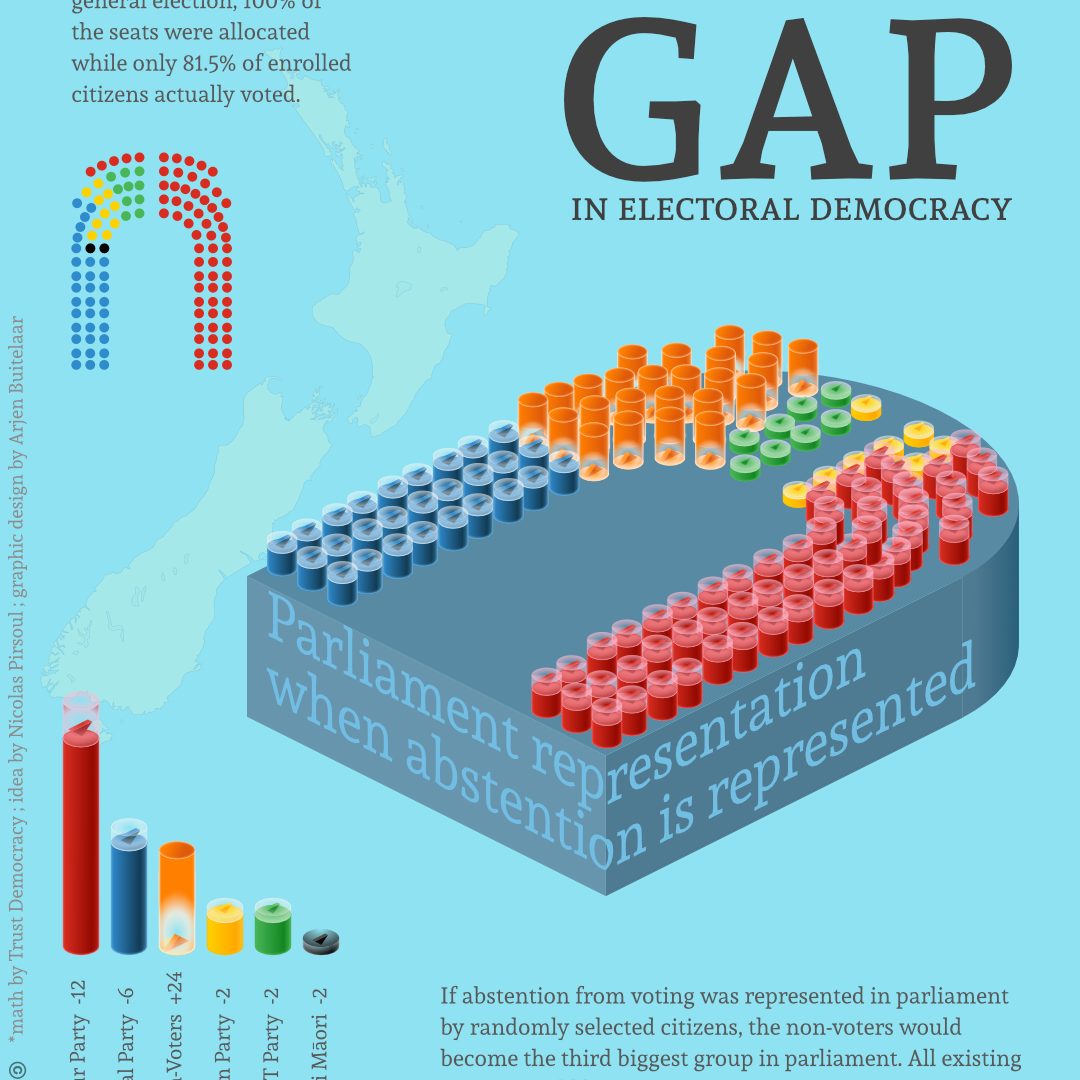

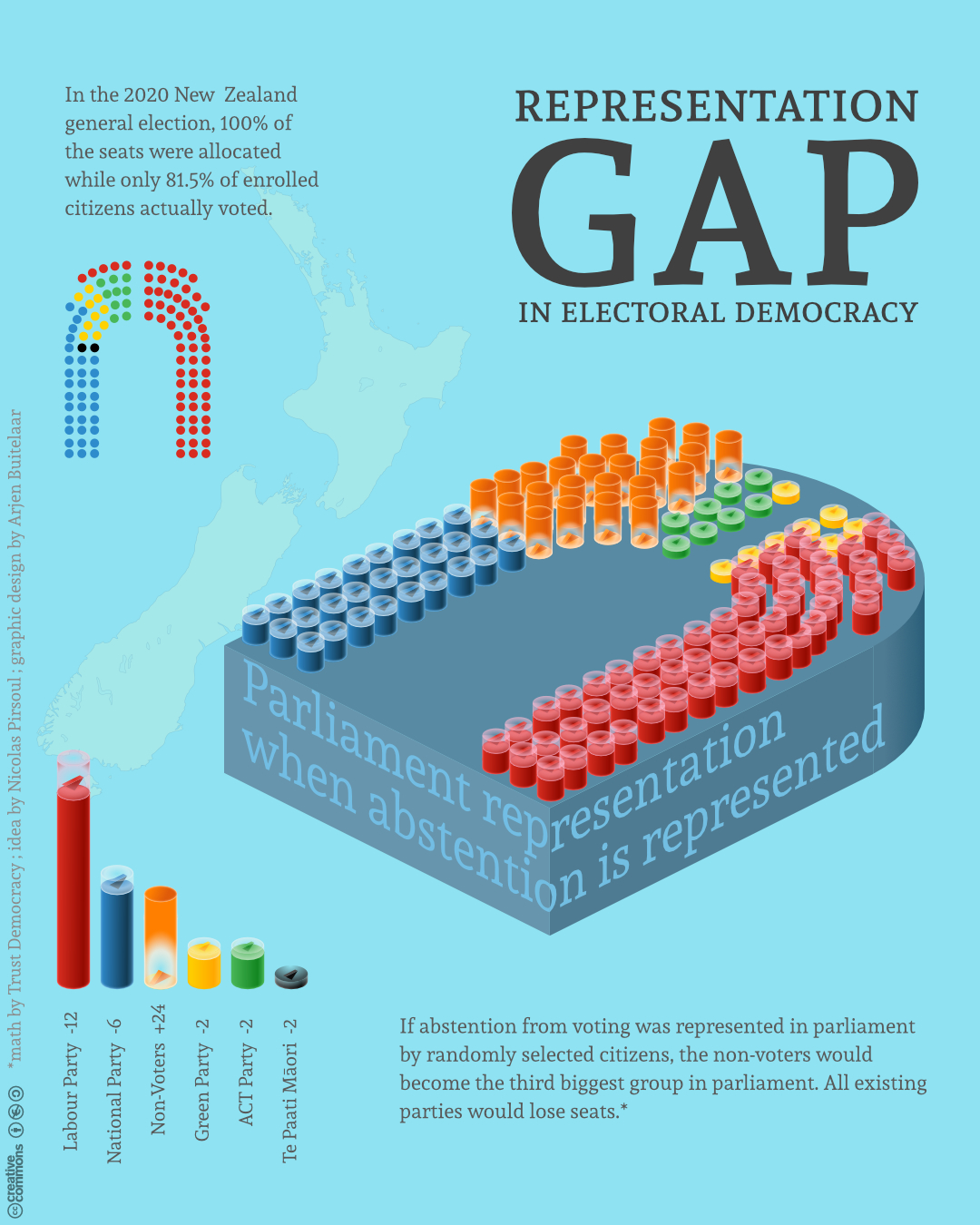

To assess what Nicolas’s idea might mean if applied in New Zealand, I decided to see what difference it would have made to the 2020 general election. The results are summarised in the infographic below and a summary of how I work this out is at the end of this post.

Over 655,000 people were enrolled but didn’t vote in the 2020 election. This is roughly equivalent to the combined populations of Wellington, Hamilton, Tauranga and Dunedin. So of course counting these non-votes would have been extremely consequential. Peeni Henare (Labour) and Rawiri Waititi (Māori Party) would not have won Tāmaki Makaurau and Waiariki respectively, and without the Waiariki seat, the Māori Party would not have its 2 representatives in parliament. In addition to this major change, the Labour Party would not have had an absolute majority and the third largest grouping would have been made up of randomly selected ordinary people.

Extending this to people who are eligible to vote but haven’t enrolled

According to the Electoral Commission, over a quarter of a million people in New Zealand are eligible to vote but haven’t enrolIed. This is roughly equivalent to the combined populations of Rotorua, New Plymouth, Invercargill, Whanganui and Gisborne.

If we extended the proposal to cover all non-voters – 655,00 enrolled and 250,000 not enrolled, or roughly a quarter of those eligible to vote – the changes to the 2020 parliament would be even more significant. I estimate that the Labour Party would have maintained a sizable majority but would have lost a considerable number of electorate seats and would not be able to govern alone. The National Party would have dropped to the third biggest party. The ‘randomly selected ordinary people’ group would have been the second biggest grouping.

How should non-voters be represented?

The legitimacy of our representative institutions falls apart if a significant number of people are not represented. It seems intolerable that almost a quarter of people who are eligible to vote have no representation in our parliament through our current electoral system and it is unbelievable that fixing this isn’t on the political agenda.

Some might say that people who don’t vote don’t deserve representation. But the finger can’t be pointed at individuals when a quarter of the entire eligible population doesn’t vote. There’s a systemic problem and it needs to be fixed.

With so many non-voters, some might argue for representing these people by having empty seats in parliament. While this might provide a powerful symbolic image about the scale of non-voting (and the legitimacy of the parliament), empty seats would likely decrease the diversity of our representatives in our parliament and decrease its ability to address today’s major challenges.

Our representatives in parliament should ideally be descriptively representative of the entire population. Compared with our pre-1996 first-past-the-post electoral system, MMP has greatly increased the diversity of our MPs but not to the extent that it is anything like the entire population. This should not surprise anyone: elections systematically favour candidates who are charismatic, wealthy, and connected. By contrast, randomly selecting representatives from the whole population is open to all on an equal basis and would, if applied in New Zealand, improve the diversity and representativeness of our parliament.

But would randomly selected people agree to become representatives? Although many would find MP salaries and benefits attractive, the role would be hugely disruptive to family, community and professional life. Perhaps these citizen representative roles would be more attractive if jobs were protected and if the terms were relatively short.

But how would these citizen representatives fare in a parliament dominated by political parties and their professional politicians? I think it would be virtually impossible to moderate the power dynamics to enable the effective participation of citizen representatives, which is why I would prefer not to mix together elected and randomly selected representatives and instead create a new upper house for the randomly selected citizen representatives. In an upper house, citizen representatives would be able to send bills and budgets back to the parliament if they were not considered in the public interest as well as have accountability and inquiry functions, both of which might be useful ways of getting issues onto the parliamentary agenda.

After note: My working

The first thing I did was visit the Electoral Commission’s statistics for the 2020 election webpage, where it was very easy to see that 2,894,486 (81.54%) of those who were enrolled to vote voted, and 655,094 (18.46%) of those who were enrolled didn’t. If we treat ‘non-votes’ as votes for a ‘randomly selected representatives party’ and assuming a 120-seat parliament, at least 22 seats – and possibly more if ‘non-votes’ also won electorate seats – would be filled by randomly selected ordinary people.

I then checked to see if ‘non-votes’ would have won any electorate seats by comparing election results with the number of enrolled people who didn’t vote for each seat. I figured it might be possible for ‘non-votes’ to win in highly competitive seats with low voter turnout but I was still surprised to find that ‘non-votes’ would have won 2 seats and that ‘non-votes’ would have been a very close second in another 2 electorates.

Given the complexity of New Zealand’s proportional system, I used the Electoral Commission’s MMP seat allocation calculator to check final seat allocations.